Humbled by Mercy: The Tax Collector’s Triumph Over Religious Pride

Luke 18:9

He [Jesus] also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt:

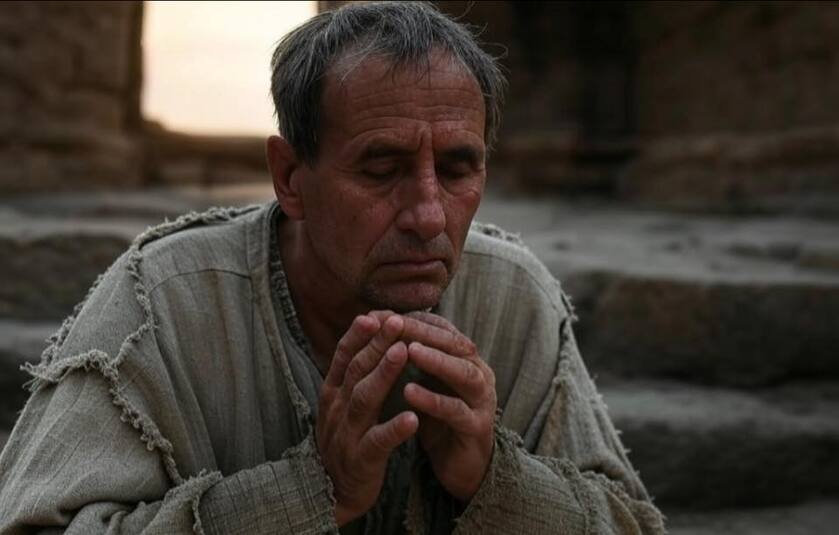

Today's scripture focus, this parable about the Pharisees and the tax collector, sets the stage by first identifying the audience. This is handy and Luke doesn't leave us wondering about its meaning either. In this parable, he describes two men praying in the temple: a Pharisee, who boasts about his own righteousness and who looks down on others, and a tax collector, who humbly asks for God’s mercy, acknowledging his sinfulness. And I think the significant thing to take away from this parable is explained by Jesus straight away.

This is the punchline:

Luke 18:14

"I tell you, this man [The Tax Collector] went down to his house justified, rather than the other. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted."

The lesson here is that justice is getting what you deserve. And the caution here is careful what you pray for, because you might get it. More like God’s justice upending human expectations. The Pharisee assumes he deserves praise for his piety, but he walks away unjustified. The tax collector, who by all cultural standards "deserves" condemnation, gets mercy instead because of his humility. It’s less about earning what’s coming to you and more about God’s grace cutting through our self-made scorecards.

So at the heart of this parable, we have the tension between the self-righteous and those who come before God humbly, not elevating themselves by virtue of their own actions. But it's more than just this, it’s not just about actions, but the heart behind them. The Pharisees religious swagger looks shiny on the outside, but it’s hollowed out by pride and scorn, where is the love. He’s not really talking to God; he’s performing for an audience of one, himself. The Pharisee’s laundry list of virtues; fasting, tithing, traditional teachings, and spiritual garb doesn’t impress God because it’s dripping with pride and contempt.

Meanwhile, the tax collector’s simple, "God, be merciful to me, a sinner," cuts straight to dependence on God, not on self. And it's the bare-naked trust in God's mercy that receives justice. And yet this seems counterintuitive. On the surface, he’s a nobody, a guy society would’ve written off. Tax collectors in Jesus’ day weren’t just IRS types; they were collaborators with Rome, skimming off extra taxes, "concessions", for themselves, despised as traitors and sinners. This dude’s not strolling into the temple with a clean slate, he’s got baggage, and he knows it. Luke 18:13 says he stands "far off," not even daring to lift his eyes to heaven, beating his chest, this is raw visceral grief over his spiritual state. His prayer is short and to the point: "God, be merciful to me, a sinner." No excuses, no spin, just a plea.

And here's the critical thing to take away from this, he brings nothing to the table. No deeds, no defense, just himself, broken and banking on God’s character. He's surrendering himself. The tax collector’s a walking paradox: a sinner who wins by losing.

Ultimately Jesus is emphasizing people who are hitching their salvation to the machinery of organized religion, and juxtaposing them against those who rely fully upon God. Jesus is drawing a hard line here: on one side, those who hitch their salvation to the gears of organized religion, its history, its rules, rituals, and status. Like the Pharisee with his polished religious machinery; on the other hand, those like the tax collector, who bypass all that and throw themselves entirely on God’s mercy, chasing after truth more than tradition. It’s a gut-punch to anyone who thinks salvation’s a byproduct of playing the religious game well. Jesus isn’t subtle, He says the one who’s justified isn’t the guy with the shiny resume, but the one who’s got nothing left but God.

I see a parallel in this today. Many folks are resting hard on the rituals, the sacraments, the incense, and the centuries of tradition, as if the sheer weight of it all guarantees their standing with God. And even more they are arrogant about that status they imagine for themselves. It's like when the Pharisees said, "God, I thank you that I am not like other men...". When people start wearing their religious heritage like a badge, imagining it locks in their status with God, it’s not just confidence, its contempt sneaking in, aimed at the "lesser" folks outside their circle. You can almost hear it: "Thank God I’ve got the true church, the real Eucharist, the unbroken line, not like those heretics or heathens."

The Pharisee’s boast wasn’t just about his deeds; it was about his identity. He's got the credentials; he's got centuries of history and tradition. He's got the trappings, and the robes literally show it. He’s not just better because he fasts or tithes; he’s better because he’s in the club, draped in its legacy. But the reality is the Pharisees aren’t really dialed into God’s sovereignty; they’re too busy curating their own. The Pharisee’s prayer isn’t about God’s power or mercy, it’s a spotlight on his own stats: "I fast, I tithe, I’m not like them." He’s the star of his own show, not God. The prayer shawls, the whole temple scene is screaming, "I’m the real deal." It’s not just that he does the right things; it’s that he is the right thing, or so he thinks.

Flip to the tax collector, no credentials, no history but a life of sin, and no fancy threads to cover up his crimes. He’s got zero to flash, so he’s got nothing to lean on but God. That’s what makes his move so stark: he’s standing there, "far off," with empty hands and a heavy heart, leaning on God because it’s all he’s got left. He’s got no empire to flex. He’s a wreck, and he knows it. And he puts God in the driver’s seat.

In this parable Jesus is jabbing at that religious mindset that turns faith into a self-help project, where the rituals, the robes, the rules become your throne, not God’s. It’s a subtle idolatry, and the tax collector’s bare-bones plea blows it all up.

But maybe this parable goes even further. Maybe it's about all systematic theologies. Take for instance the reformed crowd [where I tend to lean], big on the sola's, they might scoff at the Pharisee’s legalism, but they’ve got their own trappings that can slide into the same ditch. Think about it: the catechisms, the confessions, the precise theology, the way some cling to TULIP or the Westminster Standards like it’s their ticket in. It’s not robes or tithes, but it’s still a systematic theology of traditions and practices that start as tools to honor God but can end up as trophies to flash. "Thank God I’m not like those Arminians or charismatics, I’ve got the pure doctrine."

What I've learned is that the hardest person to reach is the religious person.

Paul said it best:

Philippians 3:8-11

"Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith—that I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead."

The religious person can be the toughest nut to crack, and Paul’s words in Philippians 3:8-11 are like a sledgehammer to that wall. The parable’s been circling this. The Pharisee is locked in his religious fortress, as are we when we lean on our own traditions, unreachable because he’s already "arrived," while the tax collector’s wide open, broken, and reachable. Paul gets it, he was that religious guy, a Pharisee of Pharisees, credentials up to his eyeballs (Philippians 3:5-6), but he chucks it all. "Everything as loss," "rubbish", strong words for his old trophies, all to grab something better: knowing Christ, not a system.

That "righteousness of my own" Paul ditches? He's spent his WHOLE life doing that. That’s the Pharisee’s game, and the reformed trap, it's the systematic theology flex. It's the righteousness of self-control. But Paul’s saying, nope, that’s not how it works. The law doesn’t save; it exposes. It’s a mirror, not a ladder.

The tax collector gets this, even if he doesn’t quote chapter and verse. He’s not listing his deeds, he’s got none to brag about, he's just begging for mercy, and banking on God, not the law. Romans 3:20 guts the Pharisee’s playbook: no amount of "works of the law" justifies anyone.

Here's the TRUTH!

Righteousness isn’t self-made; it’s God-given, through faith.

It's not just believing that Jesus lived and died and rose again from the grave. It's about trusting in his mercy and grace. It's faith. Righteousness isn’t a DIY project; it’s a gift, dropped square in your lap by God through faith. It’s not just nodding at the facts of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection like it’s a history quiz. It’s deeper, and messier: trusting in His mercy and grace, leaning into it like the tax collector, with nothing else to hold up. Faith isn’t a head game; it’s a heart-on-the-line move.

The Pharisee missed it, he trusted his own hustle, not God’s mercy. The tax collector nailed it: "God, be merciful to me, a sinner." That’s faith. Romans 3:20 and Philippians 3:8-11 back it up, no works, no trophies, just Christ. It’s the truth that slices through the religious noise: we don’t build it; we receive it.

Amen.